Article

Why Can't We Be Friends? Universities and the £1.5 Billion Collaboration Challenge

How British Universities Keep Tripping over Their Own Mortarboards on the way to saving £1.5 billion

Back in my previous dispatch I suggested—straight-faced, honest—that if UK universities would only stop elbowing one another in the ribs and buy a few mundane things together, they could shave something like £1.5 billion off the national higher-education bill. The reaction ranged from polite throat-clearing to the sort of laughter usually reserved for a vice-chancellor announcing he’s discovered student satisfaction.

The immediate retort goes like this: “We’d love to hold hands, but our royal charter won’t let us. Also, league-table season is coming and we really must focus on us.”

So let’s open the creaking oak doors, dust off the parchment and ask what the founding documents actually say about cooperation.

The Myth of the Insular Charter

Take the University of Bath’s charter, a 1960s vintage as modern as student-union posters of Che Guevara. Article 3(s) empowers the institution “to co-operate … with other Universities and Authorities … for such other purposes as the University may from time to time determine.” Warwick’s near-identical clause, drafted the same year, even supplies the helpful phrase “by means of joint boards.” Medievalists may prefer the Oxford & Cambridge Act 1571, which bestows on both universities every liberty “tending to the better increase of learning”—Elizabeth I’s sixteenth-century way of saying crack on, lads.

None of these charters obliges a university to conduct its own payroll service or procure detergent solo. Quite the reverse: they hand trustees a broad corporate power and then ask only that they pursue the public benefit. Under the Charities Act 2011 that means spending money sensibly, ideally on students and research rather than twenty-seven slightly different contracts for electricity.

Even the Higher Education & Research Act 2017—the statute that regulates everything from fee caps to whether a lecture capture counts as a miracle—stays studiously silent on joint purchasing, save for encouraging the Office for Students to share information “with any person”. In regulatory terms, the road to collaboration is as clear as a deserted library at dawn.

Evidence that it Works (when We Can Be bothered)

Proof of concept already exists. The eight regional purchasing consortia that make up UKUPC cheerfully report cashable savings of £116 million a year just on frameworks for IT kit, lab consumables and the sort of biscuits mysteriously labelled “conference”. Jisc, the sector’s collectively owned digital backbone, estimates still bigger efficiencies when universities plug into shared cloud contracts and broadband pipes rather than each reinventing the cable.

In other words, collaboration already happens; it merely stops well short of the tantalising billions.

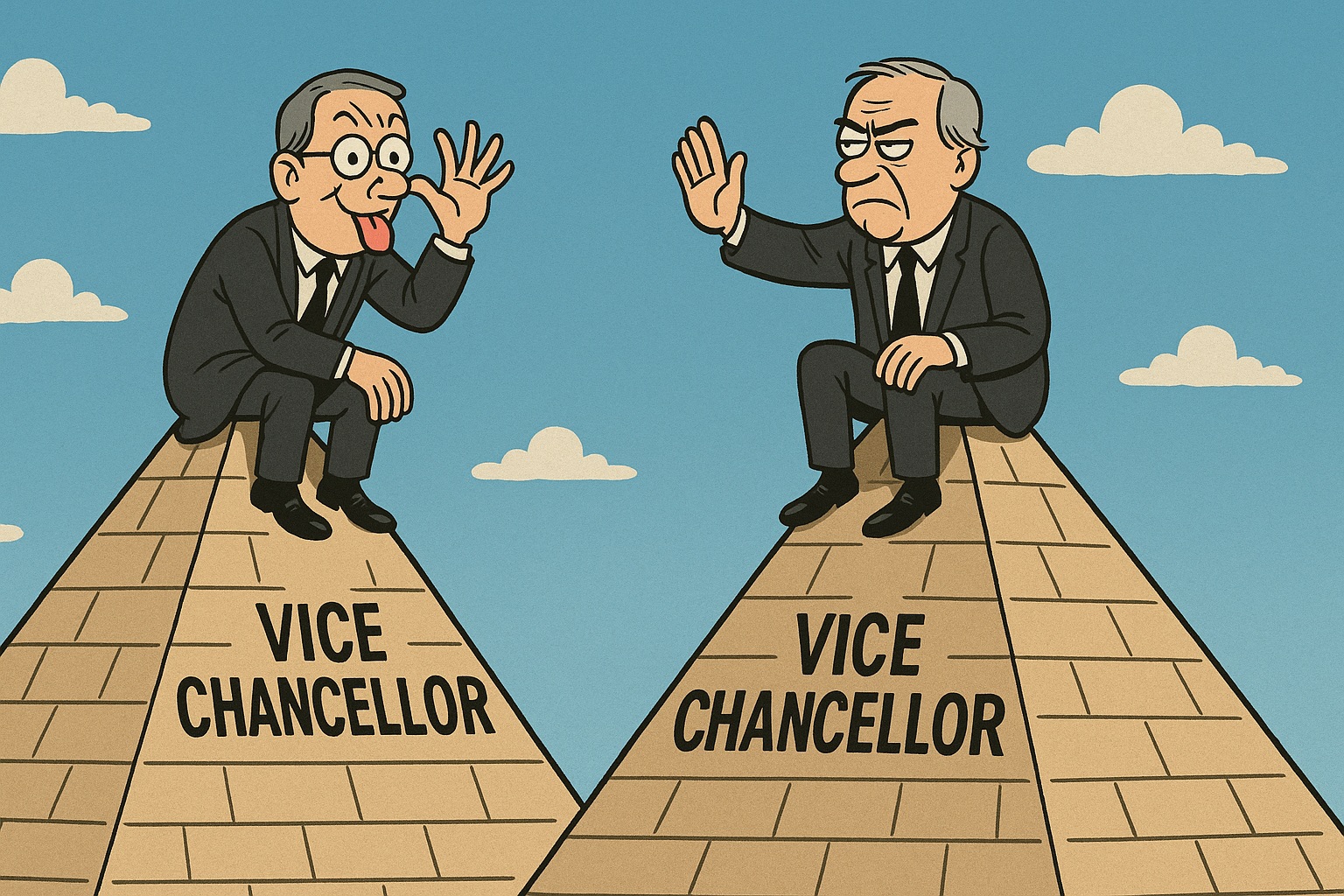

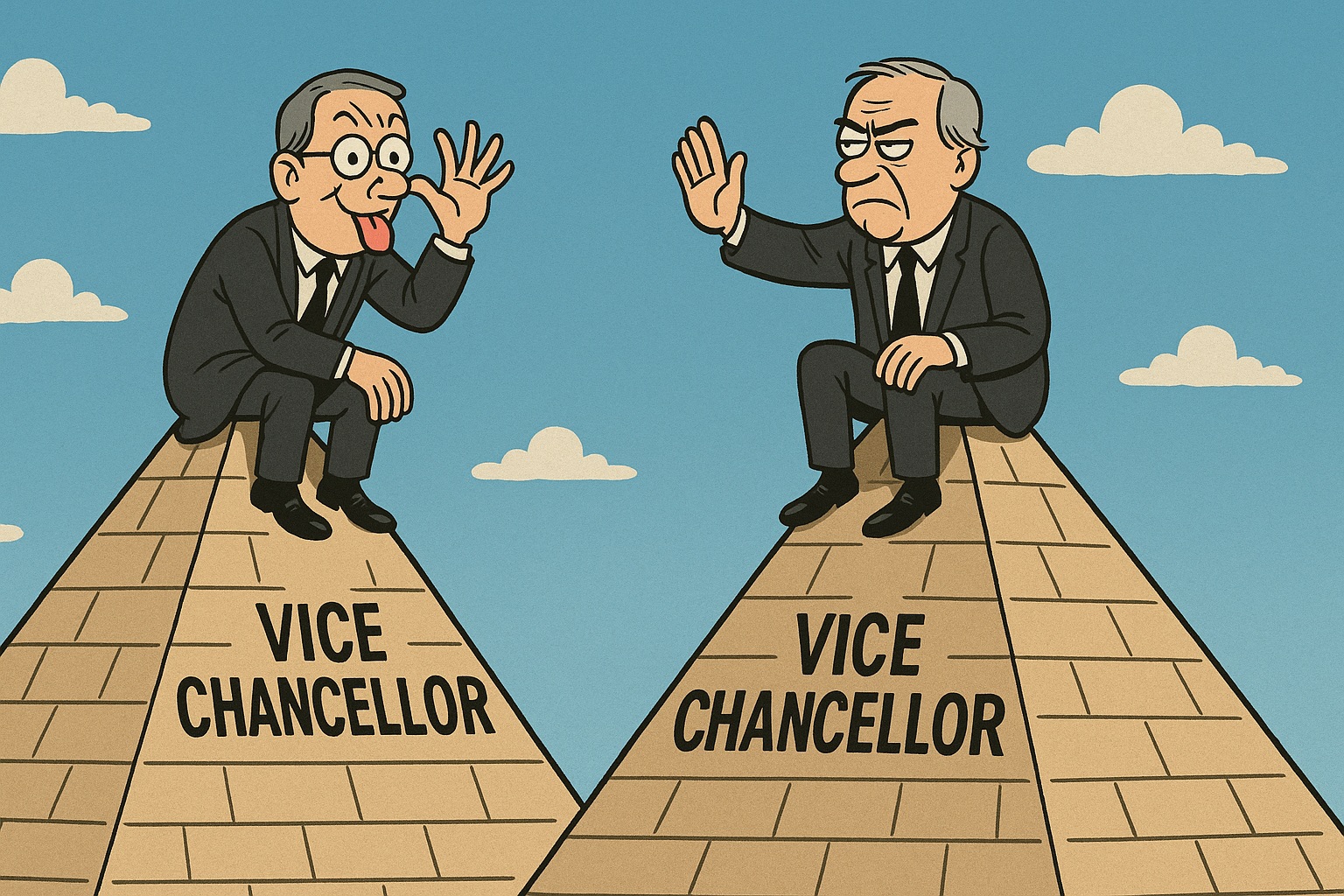

Pyramid Politics

Why, then, won’t the other ninety per cent of spend toddle into a joint catalogue? Part of the answer lies in higher education’s architectural fetish for pyramids. Each university is a neat hierarchy that tapers to a single point: the vice-chancellor. That apex owns the brand, the risk register and the annual report photograph involving an improbably shiny staircase.

Try persuading two such pyramids to overlap and, like amateur Egyptologists, you discover the points refuse to tessellate. The apexes bang together; nobody is quite sure whose logo appears first; and before long a worried registrar starts muttering about autonomy while clutching the league-table supplement.

Besides, competition is deliciously flattering. Nothing strokes an institutional ego like out-bidding the red-brick down the road for a star professor, or opening a “satellite campus” two postcodes closer to the M25. Cooperation, by contrast, is the social-science equivalent of cardigan weather: worthy, but unlikely to win you an alumni gala.

The Cultural Cul-de-sac

Culture, not charter, is therefore the choke-point. The sector talks a good game about collegiality—academic Senate, Common Room, that sort of thing—yet behaves, fiscally speaking, like a family arguing over the last roast potato. Every pound saved together is a pound that fails to show up in our margin this year, and heaven forfend the governing council should peer admiringly at someone else’s balance sheet.

The result is a kind of accidental feudalism. Twelve separate payroll offices survive because shutting eleven of them requires a committee vote in each fiefdom. Entire fleets of minivans dutifully ply their solitary routes because nobody wants to ride in a rival’s livery. And so the collective chequebook remains locked in a cabinet labelled Strategic Autonomy even while bursars complain about electricity prices.

Can the Points Be Joined?

The optimistic answer is yes, but the job is more joinery than geometry. Instead of squashing pyramids together, one builds a platform—call it a moat, since we appear stuck in the Middle Ages anyway—and lets each pyramid lower a drawbridge when it fancies cheap stationery. Jisc’s broadband, the UKUPC frameworks: these are moats already in place, proving the concept works provided nobody insists on repainting the water.

What remains is political courage. It will take a vice-chancellor bold enough to admit that another university’s procurement officer occasionally knows a bargain when she sees one. It will take governing bodies willing to measure prestige in research outputs rather than how many branded pens sit in the storeroom. And it will take the OfS to applaud savings with the same fervour it reserves for access plans and TEF medals.

A Modest Proposal (sans Brass band)

Release a sector-wide mandate: any back-office contract worth more than the average professorial salary must first be tendered through a shared framework. No compulsion to buy together—simply an obligation to see the price of solidarity before signing the solo deal. If the saving is real (spoiler: it will be) the pyramid will, in time, build its own drawbridge.

Do that and the £1.5 billion I waved about earlier stops looking like a whimsical footnote and starts resembling the future pension contributions for an entire generation of early-career academics. Suddenly cooperation isn’t woolly altruism; it’s enlightened self-interest—which, incidentally, is exactly what every charter was written to promote.

The ancient statutes did not force us into perpetual single-player mode. We chose that path, puffed up by league tables and institutional lore. The sooner we remember that the public benefit is collective, the sooner we can stop balancing the books on the shoulders of students and junior staff, and start spending the savings on something radical—like teaching.

Until then the pyramids will stand aloof, apexes glinting, each convinced it is the tallest in the desert, none quite noticing how much sand is slipping through the cracks.