Article

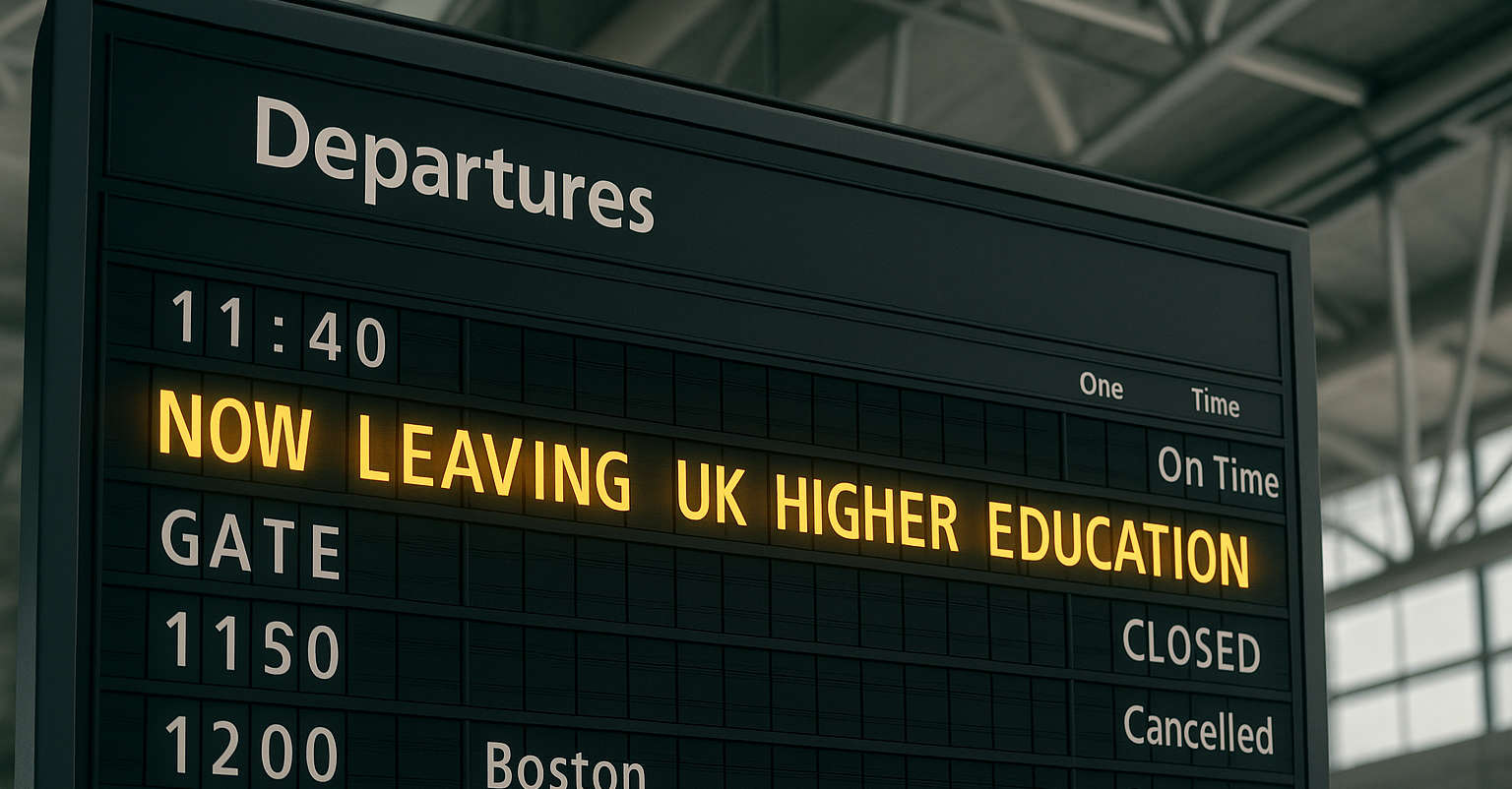

Why I'm Staying Away from UK Higher Education—For Now

Why I’m Staying Away from UK Higher Education—For Now

Originally published June 18, 2025

I have spent most of my life inside universities. As a child I remember visiting the Economics Department at Southampton University where my father worked. Economics was all V-necks and whiteboards, but downstairs was Psychology— with its labs and equipment and stuff. As a psychology undergraduate, then PhD student, postdoc, lecturer and researcher I loved the feel of these places. Places where new and good things could happen. Yet, for the first time since Tom Baker was Doctor Who, I find myself on the outside looking in. And, truth be told, I don’t plan to go back any time soon.

Below I explain why, drawing on the stark realities now facing British universities.

1. A Sector Shrinking Before Our Eyes

This academic year alone, around 10,000 academic jobs are being cut across the UK. Departments are closing, research groups are dissolving and once-thriving campuses feel eerily subdued. Even prestigious institutions are running “voluntary severance” schemes. If you’re an early-career researcher, the message is clear: the ladder has lost several rungs.

2. The Numbers No Longer Add Up

Undergraduate teaching is a loss-maker. The £9,250 fee cap (soon to creep up to £9,535) has lost nearly a third of its value in real terms since 2012. Every home student now costs a university more to teach than they bring in.

Research is deeper in the red. Last year universities in England subsidised research to the tune of £5 billion—and the hole is widening.

The only real surplus comes from international postgraduates and the beds they rent. But fresh visa restrictions and anti-migration rhetoric have already knocked overseas enrolments off course. When your entire business model relies on a market the Home Office can switch off overnight, stability is a pipe-dream.

3. Casualisation Has Become the Default

To keep the lights on, universities are turning to outsourcing and zero-hours contracts. We’re not just talking about the traditional “hourly-paid tutor”. Entire chunks of teaching are now delivered by:

- Subsidiary companies that sit outside national pension schemes

- Private “pathway” colleges that employ lecturers on lower salaries and minimal job security

- Online-programme managers who assemble global pools of gig-economy academics to run webinars and mark essays

The result is a shrinking core of permanent staff carrying ever-heavier workloads, surrounded by a ring of precarious colleagues who can be switched on and off like Wi-Fi.

4. Quality at Risk

Rising student numbers (fuelled by a demographic bulge) are colliding with a contracting workforce. Student-to-staff ratios have grown nearly 20% in a decade and are still rising. Larger classes mean less feedback, fewer contact hours and less space for the mentorship that turns a degree into an education.

Meanwhile, research time is endlessly squeezed: if your teaching is already underfunded, clearing the diary to write a grant or mentor a PhD student becomes heroic. Burnout is no longer a risk; it’s the default setting.

5. Insolvency No Longer Unthinkable

Regulators now openly discuss “orderly exits” if a university runs out of cash. In Scotland, one institution has already needed an emergency government loan; several English providers are flirting with negative reserves. Mergers—or managed shutdowns—look inevitable in the next five years. Against that backdrop, signing a permanent contract starts to feel less like job security and more like a hostage situation.

What Would Tempt Me Back?

- A sustainable funding settlement that restores the real value of teaching grants and covers the full economic cost of research

- A commitment to secure employment—because educational excellence rests on staff who can plan more than 12 months ahead

- A credible workforce strategy that values pedagogy and scholarship as much as big-ticket commercial deals

Yet, if I’m honest, the odds on any of those reforms materialising feel about the same as a Vice Chancellor taking a pay cut. Universities are drifting towards a corporate job market: targets multiply, KPIs sprout like damp dissertation footnotes, and every vacancy looks suspiciously like “same workload, smaller contract, bring your own pen.”

The trouble is we’re importing the least loveable bits of the commercial world (relentless productivity dashboards) without its compensations (competitive pay, stock options, free coffee). What the country actually needs is the reverse: a labour market where job satisfaction and work-life balance set the tone and the private sector, not academia, is scrambling to keep up. Until we stop mistaking “efficiency” for “exhaustion with extra spreadsheets,” higher education will remain a tough sell—no matter how many inspirational quotes are stapled to the staffroom noticeboard.

Until then, I’ll be deploying my skills elsewhere—still cheering on my former students, still collaborating on the odd research paper, but no longer prepared to accept precarity as the price of calling myself an academic.

I haven’t abandoned higher education; higher education has drifted away from the conditions that made it such a rewarding, if demanding, vocation. I hope one day to return. For now, I’m choosing professional stability, and I doubt I’ll be the last.

What are your thoughts on the current state of UK higher education? Have you experienced similar challenges in academia? Share your perspective in the comments or get in touch.